Each day in July, 2019, I will highlight one artwork by an artist from former Yugoslavia who left the country after the 90s and whose artworks I find interesting in relation to the phenomenology of place and the expanded notion of belonging, including the concept of inbetweenness.

July 31st

Artwork: Fabrics of Socialism, (Fototeka), 2015

Artist: Vesna Pavlovic

Text related to the exhibition of the art work at The University Art Gallery:

http://www.vesnapavlovic.com/index.php?/projects/fabrics-of-socialism-uag-sewanee/

Pavlovic mines the archive of the former Yugoslavia to explore propaganda and collective memory, the medium of photography and the life and obsolescence of media. Offering “a psychological portrait of an era burdened with photographic representation of socialist propaganda,” Pavlovic invites visitors to consider the role of photography in the fabrication and remembrance of communal identity.

As a nine year-old growing up in the former Yugoslavia, Pavlovic participated alongside thousands of others in the spectacular and carefully recorded Youth Day celebration held in 1979 in honor of President Josip Broz Tito’s 87th birthday. Her participation is captured in a film of the event housed in Tito’s official archive, held in the Museum of Yugoslavia. Individual recollection and official state record meet in the photographic image and in the archive, for Pavlovic invoking “the friction between personal and political narratives.”

In Fabrics of Socialism, photographs and footage of state events and celebrations – propagandistic images of political unity from the former Yugoslavia, a country which disintegrated into brutal sectarian violence in the early 1990s – are exposed as manufactured. Viewers are asked to consider the photographic image as a physical object, in the words of art historian Morna O’Neill “to think about not only what they see, but how they see….” Photographs, and the archives in which they are housed, are fragile. They have lives, as do the memories and official records and ideologies invested in them. For Pavlovic, “political obsolescence becomes legible as such through technological obsolescence.” Visions of state propaganda, in all their monumentality and performance of unity, are revealed to be fragile, distorted and obscured by time.

July 30th

Artwork: Letters 1 & Letters 2, 2018

Artist: Ana Pavlovic

The artist’s description of the artwork:

Both films (Letters 1 & Letter 2) are showing accounts by women migrants and their memories of early days in Denmark where the central narrative is a series of letters and photographs exchanged between Pavlovic in Copenhagen and her mother in Belgrade. Ana Pavlović was born in Serbia, but has lived in Denmark since 1999. Ana has graduated from The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen.

Text from the article by Hana Hasanbegović for MURMUR (The full version of the articel can be found on MURMUR website)

When artist Ana Pavlović was 22 years old, in 1999, she decided to leave her past in the rubble of her bombed-out Belgrade home and start a new life far to the north, in the promised lands of Scandinavia.

With the exception of an estranged cousin, she didn’t know a soul when she arrived in Copenhagen, and had no idea how she was going to make ends meet. Despite these uncertainties, however, her future looked brighter in Denmark than in the bleak and defeated Yugoslavia.

(…..)

Through the letters, we witness the development that the young women go through, as well as the experiences of the families left behind in the Balkans. We see how both sides develop coping mechanisms and survival strategies to deal with the impact of chasing a dream of a better life.

When asked how it felt working with such intimate material, Pavlović explained that she debated whether to go ahead with it or not.

“Working with personal material is very difficult and emotional, especially when it’s personal items like these. Laying out your intimate letters, family photos and life story for people to freely interpret is a little messed-up. You’re afraid you’ll be judged – but that’s exactly why this work is important!” she says.

“My goal isn’t to tell some finite story about a group of women. It’s to put the material in a new context, so that we can view it from a different perspective and on a grander scale. I’m not afraid of exposing myself and my intimate life – I’m more afraid that people won’t care about this story and these shared experiences, because they’re not unique, and they’re definitely still around.”

The film Letters 1 & Letters 2 will be show during the seminar “Looking for another space of belonging” in Copenhagen in august 2019. The seminar exploring the notion of belonging through the work of artists from former Yugoslavia – especially those who now live in what we, for lack of a better word, call a diaspora.

Speaker: Tanja Ostojić, René Block, Irfan Hošić, Rainald Schumacher, Adnan Softić, Claudia Zini, Carsten Juhl, Jeppe Wedel-Brandt and Tijana Mišković

Venue: Kunsthal Charlottenborg (cinema space at mezzanine on the 1st floor), Nyhavn 2, 1051 Copenhagen K

Please follow the link for more information:

July 29th

Artwork: Zahida is a feminist, 2016

Artist: Đejmi Hadrović

The artist’s description of the artwork:

The red thread of the project is the question of feminism in the Balkans or how it is shaped through the occidental dominant white feminism. The issue I deal with is if we can talk about emancipatory women’s practices in the Balkans, without the implications of the western category of ideological and cultural practices. If I simplify, I give voice to women who are historically completely neglected from this point of view and presented through a single prism, the prism of the patriarchy. Since the importance of their lives is pushed to the margins of anonymity and without value, I decided to do the opposite. The fact that the Balkans is described by the West and its intellectuals as patriarchal, traditional, rural, backward, mystical and scary is just one side of the story that has completely taken hold of our perception.

My free reflection on the work:

This artwork made me think about an article in which philosopher Rada Ivekovic explains that it is impossible to analyse what is the nation and the national without involving the notion of gender differences.

Rada Ivekovic argued that a feminist approach is absolutely unavoidable when trying to understand the national constructions, because the nation is initially based on the difference between the sexes, and then on a particular hierarchy between them. The gender difference is the oldest known difference in humans. It does not automatically result in social inequality, but historically it has gone that way. The difference creates a ranking, with the man at the forefront. This hierarchy is so fundamental that it is often overlooked. It is then considered natural and necessary and justifies all other types of hierarchy, be it between races, classes, religions, or nations.

Also, we linguistically connect nation to a woman: Nation means birth. The idea of a nation is about maintaining an identity and about maintaining a single lineage/stock, as pure as possible, and creating a lineage/stock happens in the relationship between the two genders. Even though this is how the nation is imagined on a symbolic plane, this is also the way it functions in reality: Territory is considered the mother body to be defended. The woman is the nation, in a very essential and material way: Her body is the nation. This is also why there have always been rapes in wars, including mass rapes. In the mass rape, the woman is not considered an individual at all – she is only a body. Thus, women become mere tools for passing on a message from one group of men to another group of men. It is as if saying: Look what we do to your women, what we do at your borders, what we do to your lineage. The notions of borders, nation, and gender are very interconnected.

Regarding primitive comunities, Rada Ivekovic said that it does not only happen in countries such as Yygoslavia where communism broke down. (free translation)

“It has to do with globalization, which, on the one hand, creates large communities like Europe, but at the same time destroys otherwise coherent systems.” “The great binary system from the time of the Cold War had collapsed, and we went back to other ‘communities’ because there was no longer a superior body that people could relate to. It is the great bankruptcy of modernity – and here I regard communism and capitalism as two figures of modernity – when they collapse, there are no politically conscious subjects that can take over immediately.” “At such a time, one is reaching for what is ‘at hand’, and these are far more primitive ‘communities’, which is not at all the same as a developed political community. Here, nationalists have free leeway, with their fantasies of a common origin and promises of a common nation. It quickly creates an identity – an identity that excludes the others.”

“They are aggressive; we just defend ourselves.” “Violence against others always starts with such a defensive language. In a matter of weeks, the common identity no longer prevailed; the universal collapsed. It was the whole patriarchal system set in motion at once. It would never have proceeded so quickly to establish these nationalisms, if not with exactly the same structure as with the patriarchy.” “It was also seen by how easily the Western countries recognized the new nations … The West reacted in an anti-communist logic, did not believe that the Communists could be retrained, and supported the nationalists because it was precisely a structure they could recognize.”

The nationalists immediately approached the women, especially in the beginning when speaking to the ‘people’, and the ‘people’ and the ‘nation’ are the same word in the Slavic languages. ‘Those who are born’ thus established the connection with the mother. Although the communists did not, they still had abstract similarities in mind. “When nationalists came to power, the first thing they did was send women back the pots and steal their basic rights, both the right to work and the right to the body (the nationalists do everything to ban abortions). The nationalists were by no means democratic that was seen in Croatia and in Serbia, and the national structure made it very difficult to make these countries truly democratic.” So, they especially have a view of feminism as something historical, rather than the idea that, for example, it is the women who have to save the world? “No, God set me free; there is no female essence. The problem with all this is that you pretend that there is a female essence, and it plays a huge role; it plays into the imaginary, and then on a political plane where it works, and that’s what’s so dreadful. “

July 28th

Artwork: Family Album, 2008

Artist: Suada Demirovic

The artist’s description of the artwork:

The artist’s description of the artwork:

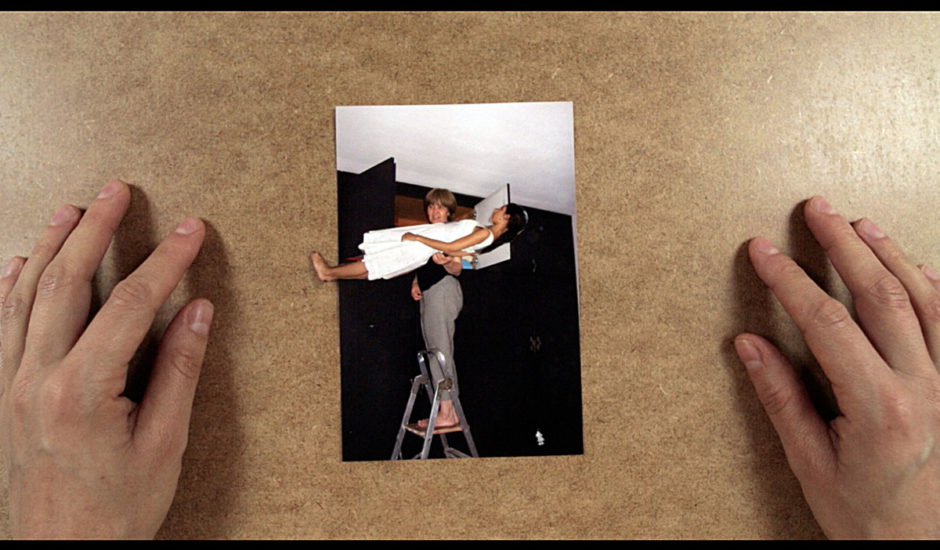

The work Family Album tells the story of my mother as a migrant. The video depicts both our hands as we go through the family album, from the year 1965 -1982; pre-1990s wartime in Yugoslavia.

In 1970 Demirovic’s mother moved to Denmark as part of a surge of guest workers. A country she had never heard of or even imagined to live in. Her journey begins with overcoming the language barrier and being hired as a guest worker in the Danish chocolate factory, Toms.

The film Family Album will be show during the seminar “Looking for another space of belonging” in Copenhagen in august 2019. The seminar exploring the notion of belonging through the work of artists from former Yugoslavia – especially those who now live in what we, for lack of a better word, call a diaspora.

Speaker: Tanja Ostojić, René Block, Irfan Hošić, Rainald Schumacher, Adnan Softić, Claudia Zini, Carsten Juhl, Jeppe Wedel-Brandt and Tijana Mišković

Venue: Kunsthal Charlottenborg (cinema space at mezzanine on the 1st floor), Nyhavn 2, 1051 Copenhagen K

Please follow the link for more information:

July 27th

Artwork: Black Flags (Displacements), 2018

Artist: Neli Ružić

The black flags, the entire century

Neli Ružić introduces me to the exhibition by quoting Giorgio Agamben: “The ones who can call themselves contemporary are only those who do not allow themselves to be blinded by the lights of the century and so manage to get a glimpse of the shadows in those lights, of their intimate obscurity. The contemporary is the one whose eyes are struck by the beam of darkness that comes from his own time.” This is instrumental for the understanding of the scene in question. The single-room exhibition space of SC Gallery is mostly filled with flags hanging from high ceiling to the floor creating a

static, scenographical ambience…the flags are arranged upright using stones which keep them in place thus blocking unrest of their likely fluttering. The stones are large, rough, earth-toned, from her native island of Šolta, thus carrying rural connotations and contrasting the scene in which they appear as well as the purity of the exhibiting space. The ambience is theatrically illuminated using a reflector strong enough to dim the space between the flags; and used old suitcases are placed within the shaded fields just open enough for small amount light to peep from their interior. What migrations is Neli Ružić speaking of, in the country of constant, economic, political, difficult emigrations and country that witnesses continuous exodus with half-empty suitcases? She is speaking of their persistence, continuous departures and partings that she experienced, too. She is speaking during the intense debate about the controversial upcoming migrant wave. Traces of light piercing from suitcases and reminding of different historical epochs suggest that life always finds a way. The simplicity of the sight and leanness of elements and symbols Ružić employs to communicate with the observer only stress the intensity of experience. Everything fits into only four elements: flags, stones, suitcases and light-darkness, the century-old burden of social, political and migration weights.

Excerpt from curatorial text by Janka Vukmir

July 26th

Artwork: Kulisa, 2012

Artist: Alen Aligrudic

Kulisa, 2012, 120×60 cm Satin matt laminated lambda print on dibond 3+1AP. From the series “Paradigm Metamorphoses – Un Familiar Ities”

The artist’s description of the artwork:

“On the new side of the town, there is a replica of the old city. It looks like a coulisse for a movie and has become the city decoration and one part of the public urbanization project. Since the coulisse is there, anyhow, the movie is about to be made. Or is it the other way around?” text from the booklet VA03 (Visuel Arkivering 03)

My free reflection on the work:

A couple of years ago, an artist friend of mine from Bosnia used a coulisse as a metaphor, in order to explain how the regime shift and the sudden civil war situation in Yugoslavia had clearly left a lasting trace on his orientation in the world around him and his critical thinking. “Once you have seen the backdrop-coulisse fall down and you have discovered that the society you all your life have believed to be the reality is actually a constructed coulisse, you simply lose the innocence and naivety in your perception of the world.” He said, “some kind of scepticism grows on you, and from that moment on you start questioning your surroundings, always looking behind “the coulisse”, checking the backside of the society being played out on the stage.

As a consequence of a change in the regime in his home country, he stopped taking societal system and organization models for granted and started being more critical towards them in a healthy form of scepticism. I say healthy because I consider critical thinking to be a positive artistic quality that can make other people start questioning conditions that they otherwise might overlook and face the problems that otherwise would remain unnoticed by them. Seeing things from different perspectives is also an important curatorial ability, and the coulisse metaphor can also be used to illustrate the curator’s work of creating an image out of images – a reality within reality.

From The Curatorial: A Philosophy of Curating edited by Jean-Paul Martinon:

“The imaginative space of a nexus of pictures that emerges in the gallery accordingly indicates not only the transition from the accumulation of curiosities to the taxonomical arrangement of pictures based on their size, themes or genres or to the schools of painting they exemplify but also the emergence of a particular space composed of pictures. The “theatrum picture” – coulisse-like picture-wall, superimpositions of pictures of pictures resembling collage and sequences of picture-spaces folded in the manner of a house of cards- becomes the defining metaphor of this space.

Rene Margtitte is therefore not the first to conceive this picture-space as the ineluctable horizon of thinking before which pictures always refer only to other pictures. Even in the seventeenth century, this special space of representation refers first and foremost to itself, the representation of a representation. Yet, in doing so, it depicts not only self-rereferentially itself, it also includes specific forms of relations in its field of vision: relations between the concrete picture-space and the space of pictures, between the people who populate the picture-space (the painter and the prince for example ), between them and the spaces and pictures to which each is assigned and finally between the picture space/space of pictures and an exterior space, which is in the most instances only hinted at. The selection of the pictures and the way they are arranged increasingly also come to define the volatile power of these relations on the level of substance. Starting in the eighteenth century, the growing historical dimension in the particular swells his space of imagination to a phantasmatic magnitude into which reflections on the meaning of history, on precesses of the formation of consciousness and on psychological dispositions find themselves. Giovallni Nattista Pranesi, notably, reinterprets the accumulation of historic remnants into pictures of the internalization of imperial space. A thread leads from there to the abysmal collection in John Soane, and finally to that peculiar collector, Sigmund Freud, who will translate the space of the collection into a topology of psychological functions.”

July 25th

Artwork: Misplaced Women?, ongoing since 2009

Artist: Tanja Ostojić

The artist’s description of the artwork as stated on the project blog

Misplaced Women? is an ongoing art project by Tanja Ostojić, Berlin based internationally renowned performance and interdisciplinary artist of Serbian origin. The project consists of performances, performance series, workshops and delegated performances, ongoing since 2009, including contributions by international artists, students and people from divers backgrounds. Within this project we embody and enact some of everyday life activity that signifies a displacement as common to transients, migrants, war and disaster refugees, as it is to the itinerant artists travelling the world to earn their living. Those performances are continuing themes of migration, desired mobility, and relations of power and vulnerability in regards to the mobile and in the first line female body as in numerous previous works of mine.

Participants are invited to perform Misplaced Women? and to share there experiences on the web blog and during public discussions. Locations for performances suggested include migration specific places: train stations, airports, borders, underground, police stations, refugee camps, specific parks, prisons, etc. Contributions are posted in the form of images, notes, stories or videos to the projects blog: https://misplacedwomen.wordpress.com/ There are over 90 blog entires published since 2009.

While contributing to one of group performances or a performance of their own, participants get an opportunity to develop sensibilities for related issues and processes, and that´s the point where in my opinion important questions start to open up. The results of the workshop are as important as the processes them self that are being documented, archived and written about by most of the participants. Sometimes very valuable contributions occur, such as “coming out” by Marta Nitecka Barche of Polish origin, doctoral student from the University of Aberdeen who spent three weeks in a regular prison in the USA several years earlier because her visa expired. She wrote about humiliation and shame she experienced in regard to this administrative problem, that has been dealt with while she was handcuffed and ankle-cuffed. Marta´s story has been archived in the section Stories of the project web-blog.

July 24th

Artwork: Multiculturalists, please deal with the danish racism and leave us foreigners alone, 2018 Artist: Nermin Durakovic

“Multiculturalists, please deal with the danish racism and leave us foreigners alone” is a poster-project in public space realised in Copenhagen in 2018.

My free reflection on the work:

This artwork is a comment to a slogan by the art group Superflex “Foreigners, please don’t leave us alone with the Danes” – a slogan which ”looks good” as a foreigner-friendly poster-artwork but is problematic as an authentic welcoming message to foreigners.

In 2014 I discussed this artwork with a group called The Art Delegation. It was a community of non-Danish artists actively working and leaving in Denmark. Together, the members of The Art Delegation visited exhibition venues trying to understand, map and give feed back on the infrastructure of the Danish art scene and detect intercultural problems within it.

Orsolya Bagala, one of the delegation members made an interesting point about the Superfelex’ statement and what effect it had on her the first time she saw it. She said that, it seamed provoking, because it was pointing at her as a foreigner by asking her not to leave, instead of pointing at the people who were forcing foreigners to leave. “The foreigners never wanted to leave”, she said, “but some of them simply got kicked out.” The second observation made by The Art Delegation members was about the very populistic way of using the poster. For some years ago, when the poster was published for the first time, many people started using it, even politicians, but not many of them really tried to make a change in their behavior in order to include the foreigners in their real life. So the poster was a catchy slogan and a very light critic that made it easy for people to be right-wing-ish, without risking anything or sharing their benefits with foreigners.

July 23rd

Artwork: Walking on the Water According to Dr. Knaipp, 1997

Artist: Nada Prlja

Usually I had an immediate attraction to this image. I likely fell for it image because of its archive-like, nostalgic expression. And when I found out that it is an early work by Nada Prlja, which was connected to the Institute of Physical Rehabilitation in Skopje, I started reflecting on city and healing. The city shapes the people living there while it, at the same time, is shaped by them. It is a two-way reaction – a symbiosis between a space and a person inhabiting it. If the body is what connects people to a space, then a physical rehabilitation is the method of fixing the synchronization between body and space. In this specific image, there is an arm being fixed.

When I looked closer into the project “Walking on the Water According to Dr. Knaipp”, I found out that the physical body in this work was almost absent and replaced with the idea of ghostlike-presence and fluidity. This only opened up further interpretations regarding our sense of belonging on several levels across time and space.

Walking on the water according to Dr. Kneipp from Nada Prlja on Vimeo.

A text by Liljana Nedelkovska (Curator at NI Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje, Macedonia)

Skopje, October 2008

Nada Prlja started her artistic activity at the end of the 1990’s with a series of solo exhibitions in Skopje. Amongst these was the exhibition entitled Walking on Cold Water According to Dr. Kneipp, installed within the Institute of Physical Rehabilitation in Skopje, in 1997. This installation/exhibition functioned as a reenactment of the therapeutic healing methods developed by Dr. Kneipp, an 18th century Bavarian priest and practitioner of alternative medicine (hydrotherapy). In one of the institute’s spaces, a series of female nightgowns were positioned (apparently floating) in large, water-filled concrete basins; the white nightgowns were imprinted, in the area of the chest/heart, with drawings of Dr.Kneipp’s healing methods. In an adjacent space, floating above a vast metallic tub for water treatment, another nightgown was installed onto which, instead of an imprinted drawing, the flickering image of a video was projected. The video consisted of a series of repetitive, dreamlike sequences of images of the real spaces of the institute itself.

What was so very fascinating about this particular exhibition was precisely the combination between the fragility and vulnerability of the represented body (the sensuality, sadness, fear, pain, and melancholy imprinted on the whiteness of the gowns) with the incredible and somewhat daunting presence of the real space itself, with its inner layout and architecture. This combination was visually highlighted by the transition from the real towards the virtual space as the topography of the space (with its angles, curves and condensed diagonals) was projected, through a video beam, onto the region of the ‘body’, marking thereby not only its exteriority but also its interiority. What is crucial here is the transition towards interiority, towards that which could be described as pure subjectivisation: the subject as the impression of reality, or rather, the impression of reality as an inner map of the process of subjectivisation and identification. And there – where one would expect to find a sense of fulfillment and density, a firm inner support – instead, paradoxically, a void or rift appears, a line of externalization. An inner distance, which cannot be surpassed. This is why the wound can never heal, and the pain cannot disappear.

We also find the logic of the ‘rift’ in Globalwood, the project that Nada Prlja realised at Mala Stanica, the Macedonian National Gallery, in 2007, after a ten-year period of absence from the Macedonian art scene. In Walking on Cold Water According to Dr. Kneipp, this logic can be seen as the conceptual background of the artistic strategy in order to review the position of the postmodern subject (characterized by decentralisation, dislocation and passivity). In Globalwood, however, the notion of the rift is conceptualized with the intention of reviewing the post-Yugo-slav, post-socialist countries in the Balkans, by reflecting on the negative cultural phenomena, which characterise the so-called period of transition – the transition from the realism of socialism towards a democratic liberalism. Macedonia, after the fall of the socialist (communist) ideology, reoriented itself towards an almost obsessive consumption of the western ‘ideology’ – capital, albeit in an explicitly pre-modern manner. For already two decades, Macedonia has been caught in the rift between these two options – between Europe as a desired place and Europe as an unreachable place. Within this structural imbalance, in this rift that destabilizes and unsettles society from within, a variety of apparitions and phantoms, or ‘dark objects of desire’, have moved in. These ‘dark objects of desire’ are: the turbofolk phenomenon, various macho and show-business icons, monumental statues and various ‘superficial urban interventions’ which, rather ghostlike, occupy the public space of the city – mythical narratives and monstrous nationalist identifications. Globalwood takes a critical and provocative position in relation to these socio-cultural phenomena, which, like specific endemic conditions, add to the already negative perception of the Balkans harboured by the West. The intentionally emphasized visual and discursive contrasts – themes on which the articulation of the entire project was based (such as local/global, low culture/high culture) – seem, at first glance, to be merely ironic accentuations of the already too obvious and visible. An example of this is Prlja’s response to the huge neon cross on the summit of Mount Vodno which lit up, at night, assumes a ghostly dimension. Nada Prlja challenged this monumental cross with a ‘counter’ public art work – a large neon sign comprising her own initials, positioned on the highest point of the gallery’s roof. Another work that illustrates the same approach is Prlja’s competition-performance between aspiring stars of the turbo-folk musical genre against a jury comprising of well-known art historians and theoreticians.

The critical potential of the work was directed not so much towards the visible, than at the less visible elements where the ‘virtual’ game of capital and power is played out, and towards those hidden mechanisms in society which, in reality, allow and stimulate that very process of ‘turbo metastasis’. All of these displacements which, like phantasmagorical growths, multiply and spread themselves onto/within the collective body, weaken thereby the possibility for more meaning-ful changes to occur in the value system; these are not phenomena that evolve outside of the sociopolitical reality, but instead are political means through which society executes its reality. However, this is not about the reality of everyday life (as the reality of society and people involved in the process of production and consumption of cultural products). Instead, it is about reality as something Real (of which Lacan speaks when making a distinction between reality and the Real), as the abstract, ghostly logic of power and capital, which defines the sociocultural actuality.

In an interview that was held in relation to this project, Nada Prlja was asked whether or not her perception of Macedonia is a perception from a distance, from afar (Prlja has been living in London since 1999). Her response was as follows: ‘The fact that I am never in one single environment, sharpens my senses. However, the sharpness of the senses is two-sided and is relevant for both England and Macedonia / the Balkans. It is about a rather unusual form of existence. Every day I have a yearning ‘to go home’, but where is ‘home’ now?’ 1 ‘Where is ‘home’ now?’ This is a question which Nada Prlja indirectly poses in her project Should I Stay or Should I Go?, realised at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje in 2008. The question of the exhibition title Should I Stay or Should I Go? (borrowed from the title of a song by The Clash, from their 1982 album Combat Rock), is not being asked, in the context of the exhibition, as a question which encompasses someone else as a decision maker, someone else from whom one seeks a preconceived reaction that could provoke a decision, an answer that would solve the dilemma – whether to stay or to leave. The question here is being asked by a subject who is alone with himself, who asks the same question of himself, of himself for himself: whether or not, despite the misery to which the subject is exposed in his own country, should stay there, or alternatively to escape far away, there in the West, there where ‘life is for living’. Nada Prlja conceptualizes this question through the existential status of the Mace-donian worker – in this case, the employees of factories from the textile industry, who are involved in the production of clothing items for western companies such as Hugo Boss, Mango, etc. As Nada Prlja says: “In that process, these workers are literally exploited in an environment in which many of the human rights and workers’ rights are not being respected (long working hours, lower wages, etc.). Many of these workers believe that there is no hope for a better life under such conditions – a feeling of despair that is often resolved through their decision to emigrate (often illegally) in search for better conditions and a better future.” 2 But that is exactly where the real problems start. The search for a better life often ends in some sort of institutionalised shelter for the “multicultural refuse of history… This bitter experience is accepted in order to avoid the assumed dread of returning to the place from which they have been forced to flee. In their eyes, the West is portrayed as a lie, a total deception, and becomes the subject of open hatred”. 3 However, even if they were to succeed in emigrating, the workers will never succeed in becomingintegrated within the New World, to become equal citizens; there, they will always remain foreigners. And, as Slavoj Zizek says, “foreigners can look like us and work just like us, but there is that certain unreachable ‘je ne sais quoi’, that something in them ‘that is more than themselves’, and because of which they are not ‘entirely human’. 4 That which is ’more than themselves’ is what irritates, that which needs to be erased and destroyed, to be expelled. Through reviewing and articulating the status of the Macedonian workers (which in our society acts as a kind of ‘remnant by inertia’ that needs to be suppressed and put into brackets), Nada Prlja is, in reality, taking a critical position in relation to the stereotypical view of New Europe as a place of freedom, justice and economic prosperity, a place onto which is projected the desire of a better future by all those who are not yet within its borders. In order to develop and communicate her idea, the artist uses several artistic processes and combinations in various disciplines and means of expression (installation, video, performance), creating thereby a complex exhibition, which includes the following elements/works: An installation of sewing machines as a ready made approach to the recreation of a real situation: a factory ambience, dislocated and recreated within the museum space. A live art event (performance) in which Prlja, together with a group of fac-tory workers (employed in the textile company MakJeans) took part in the manufacture/production of a series of T-shirts, the workers produced the shirts while the artist designed them, writing/painting onto them various phrases and slogans regarding foreigners, that appear in the press and legal documents in western countries, such as: Send ‘em Back, Legal Alien, Bloody Foreigner, etc.

Another installation, Queue, refers to the typical airport environment in which black ribbon barriers are positioned in a manner to direct the movement of travellers towards the control points (where they are thoroughly searched as a way of ‘measuring of life’, controls which are made on all those citizens coming from the other side of the ‘Shengen wall’). This procedure automatically marks those citizens as suspicious, as those who need to be thoroughly checked and undergo a detailed search – in a manner which brings in question the privacy of their bodies; a procedure which Giorgio Agamben terms as biopolitical tattooing. The exhibition features three video projections that in different ways articulate and review the position of foreigners and their reality: Rights is a series of videos in which children, originating from the countries of New Europe but now living in Western Europe, read out aloud, with difficulty, the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Freedoms; West is a video that, metaphorically speaking, refers to the erasure of a whole world known as Eastern Europe; and Give ‘em Hell!, a video that, in referring to the aestheticised violence from Stanley Kubrick’s film A Clockwork Orange, reviews the reality of violence in contemporary society. Finally, the installation piece Art Lessons for Invisible Children is a series of photographs and drawings that refers to the subject of the invisibility of illegal immigrants. With all of these works and approaches that comprise the project in the Museum of Contemporary Art, Nada Prlja reacts critically to the realities of contemporary society, on both a local and a global level, with which she consciously undermines the traditional notion of artistic representation. Neglecting the coefficient of artistic visibility (that which we have become used to seeing/interpreting as art), here the ‘art’ is created with a somewhat different energy that is directed not towards the art world but towards the world of reality. The intention is not to make art objects to be positioned as ‘art’ in some neutral separated territory (the Museum), but to express a personal standpoint as an artistic strategy whose visual potential is intended to be used as a critique, a position of resistance, disagreement.

Thinking about art in terms of its specific competence (means) and not in terms of its specific goals (art works), Nada Prlja insists on the transgressive aspects of the artistic act, on its efficiency and impact, with the aim of ‘raising the general public’s awareness about the fact that the aforementioned condition could have a permanent influence/effect on the manner in which the future is shaped’

1 Interview with Nada Prlja by Michelle Robecchi, Nada Prlja, Globalwood, Skopje: National Gallery of Macedonija, 2007 (text from the exhibition catalogue)

2 Project description; Should I Stay or Should I Go, Nada Prlja

3 Prisoners of a Global Paranoia; Zarko Paic, Art-e-Fact: Strategies of Resistance(Internet magazine for contemporary art and culture), no.1

4 Interrogating the Real; Slavoj Zizek, Publisher: Novi Sad: Akademska knjiga, 2008, pp.313

July 22nd

Artwork: Repriza/Uzvracanje (Reprise/Response), 2018

Artist: Damir Avdagić

The artist’s description of the artwork:

In “Repriza/Uzvracanje (Reprise/Response)” 4 people in their mid-60s, originally from Ex-Yugoslavia, perform a transcribed conversation from the piece “Reenactment/Process” from 2016 in which four people in their mid-20s discuss the inter-generational frictions they experience between themselves and their parents, relating to the conflict in Ex-Yugoslavia.

The participants in “Repriza/Uzvracanje (Reprise/Response)” perform the transcribed conversation and react to the content, commenting on issues of responsibility, guilt, shame and and the legacy of communism in the wake of the conflict.

“Reenactment/Process” from 2016 and “Repriza/Uzvracanje (Reprise/Response)” from 2018 make up a body of work that stretches a historical time period between two generations and reflects on how the past echoes in the present.

………………………………………………

The film Repriza/Uzvracanje (Reprise/Response) will be show during the seminar “Looking for another space of belonging” in Copenhagen in august 2019. The seminar exploring the notion of belonging through the work of artists from former Yugoslavia – especially those who left the country after the 90’s

Speaker: Tanja Ostojić, René Block, Irfan Hošić, Rainald Schumacher, Adnan Softić, Claudia Zini, Carsten Juhl, Jeppe Wedel-Brandt and Tijana Mišković

Venue: Kunsthal Charlottenborg (cinema space at mezzanine on the 1st floor), Nyhavn 2, 1051 Copenhagen K

Please follow the link for more information:

July 21st

Artwork: Bigger Than Life

Artist: Adnan Softic

The artist’s description of the artwork:

In Skopje, a government plan costing several hundred million euros is creating a brand new, ancient city center; the project is called “Skopje 2014.” So far, some thirty government buildings and museums, as well as countless monuments in the classic style have been erected in the Macedonian capital, in an attempt to put Skopje on a par with Rome and Athens. In some cases, existing socialist structures were incorporated into the new builds.

A city looks for a future in history – Macedonia is inventing itself as a nation with historical status based on a model of antiquity that never existed in that form. Would that be something new? Will we buy that (hi)story?

In “Bigger Than Life” present-day Skopje becomes an archaeological dig. We can follow in real time how history is made, how antiquity is constructed, how historical singularities are manufactured via mimicry, and how the boundary between truth and falsification becomes blurred the minute something is recorded often enough on postcards.

A variety of differing ways of looking at the ongoing construction in Skopje produces a puzzle about multi-ethnic states and the phantasm of national purity, about romanticism and love, the relationship between personal memories and collective memory, and about how a history built on empty claims can actually take on substance.

AUTHOR, DIRECTOR: Adnan Softić,

CINEMATOGRAPHY: Helena Wittmann, Adnan Softić,

EDITING: Nina Softić,

MUSIC: Daniel Dominguez Teruel, Adnan Softić,

SINGERS: Alexey Liosha Kokhanov, Pauline Jacob…

………………………………………………

The film will be show during the seminar “Looking for another space of belonging” in Copenhagen in august 2019. The seminar exploring the notion of belonging through the work of artists from former Yugoslavia – especially those who left the country after the 90’s

Speaker: Tanja Ostojić, René Block, Irfan Hošić, Rainald Schumacher, Adnan Softić, Claudia Zini, Carsten Juhl, Jeppe Wedel-Brandt and Tijana Mišković

Venue: Kunsthal Charlottenborg (cinema space at mezzanine on the 1st floor), Nyhavn 2, 1051 Copenhagen K

Please follow the link for more information:

July 2oth

Artwork: Greetings from Montenegro 2007-2009

Artist: Alen Aligrudic

The artist’s description of the artwork:

In 2006 Montenegro was the last of the republics in the former Yugoslavia to proclaim its independence. Alen Aligrudic wanted to document the changes after that historic moment, and travelled through the largely empty country. It faces a future which, according to him, is anything but rosy. From the first day of independence, foreign investors have been buying up the land and real estate. The Mediterranean climate makes the ground so desirable that the lure of turning a quick profit on it has now destroyed rural life and the agrarian sector. At the same time the change-over to a knowledge and service economy has proven difficult. Many former residents of the countryside are also moving to the coast or the capital, Podgorica, leaving rural areas even more depopulated than they were before.

My free reflection on the work:

At the moment, I’m in Svedborg – a harbour town in southern Denmark. Several times a day I go to the sea and look at the boats. The question that has been circling my mind for the last couple of days has been What is local, and what is global? Or What do I consider local vs. global?

And I can feel that maybe watching the sea from the harbour is slowly changing my vision of locality. At least, the water reflections make me reflect on my positioning and belonging to a place.

Often I feel my personal feeling of belonging is based on experiences. This feeling could also be called “experiential nearness”, and it is characterized by the fact that it functions across space and time. Sometimes I can feel (both sentimentally and practically) more connected to places and people far away from me or to historical moments that took place far before I was born. I guess most people have a similar feeling from time to time. This is experiential locality, which goes beyond physical reality. It is an open kind of particular locality, which, for a moment, could look like the idealized concept of universality.

While I’m sitting on the harbour and watching the sea, several times I’m hit by an almost physical feeling of wanting to sail away, to travel away into the unknown open sea and leave the local position behind. My friend who lives in Svendborg tells me often about the many wives of local sailors who stayed home “on land” while their husbands were “at sea”. These women must have had the same adventurous necessity to travel and sail away.

Maybe they were sitting at the very same spot watching over the same horizon as I am. They probably worried sometimes about their husbands, trying to look for a silhouette of a ship arriving in the distance. But I’m sure that other times, they dreamed away in a spirit of wanderlust, driven by a desire to detach themselves from the local anchor and embark upon new adventures in the wide-open sea. It is impressive how the sea makes us dream away from the local into something more universal.

Alen Aligrudic’s photograph came to my mind several times today. Sometimes I felt like I was the big rock in his artwork – stocked, heavy, and unmovable, but wanting to sail away in the open sea. And in the other moments, I was thinking that the rock is not a physical thing, but a living being that represents an accumulation of our experiences. The more we experience, the more open our locality becomes. In this case, the growing massiveness of the rock was positive.

July 19th

Artwork: The Didactic Wall, 2019

Artist: Mladen Miljanovic

For two days ago I came back to Copenhagen after spending two short days in the border town of Bihac, where the refugees are trying to cross the border from Bosnia to Croatia daily. I took part in a roundtable discussion organized by curator, Irfan Hošić in connection to the Mladen Miljanovic exhibition.

During the event, I was looking at the long gallery space. On one side there was a wall with the relief-like artwork in shiny stone and with drawings of people moving through the border zone. On the other side, there were windows, more or less similar in size to the artwork, through which one could see people walking up and down the pedestrian street. It was like seeing a mirror reflection with a twist, showing art on one side and the reality on the other.

Then it was my turn to answer one of Irfan’s questions at the roundtable, and I brought up the notion of Limbo as an in-between space (something that later that day – thanks to Ajla Borozan and other reflective participants of Kuma International – provoked an interesting discussion about my interpretation of the refugee situation at the moment, in which I had to explain that I was not overlooking the urgency and necessity of solving the problem of refugees, and that my point was not arrogantly to use a Christian term to justify the devastating feeling of ”being in the limbo”, but rather to use Limbo as a model for thinking about and imagining the third space.)

Suddenly a woman from the audience said that in the building just across the street from the gallery, at that very same moment, local politicians were also debating the refugee situation, but from a very different point of view; Instead of creating helping manuals for survival, they were trying to develop rules and “manuals” for making life more difficult for the refugees. I thought to myself that maybe we should go there and demonstrate or that we should invite them here to listen to our visions.

That is when I discovered that we were sitting in the Limbo-space of in-betweenness I was referring to – Gradska Galerija Bihać was exactly between the two realities, acting as a bridge between the artwork that tries to relate to the world outside the gallery and the window to the world outside pushing its way into the gallery.

Actually, Bihać itself is the “third space” where constructive reflections can take place. Exactly because it is a place of tension, grey-zone, uncertainty, and even conflicts, it can be the place of potentiality with important reflections and discussion, just as this exhibition and roundtable debate was attempting to be. We know that crises often generate creativity and inventive visions. Thinking in this way, it could be possible to transform the frustrating situation in Bihać into a situation for pioneering thinking in new directions and models that can help solve the alarming local situation but also be useful beyond the local context.

It is not easy to deal with urgent migration problems through art; it automatically activates problematic questions regarding ethics, empathy, the role of the artist in society, the potential of art to make a socio-political change, etc. Coming from the world of art and culture, one might easily end up making several unsuccessful attempts before finding a meaningful form to deal with the burning issues of our society. But it is important and brave to try. This is why I would like to support Mladen, Irfan as well as the team of Gradska Galerija Bihać. Thanks for being brave and trying to create meaningful and reflective art projects within this complex “space of Limbo”.

The curator of the exhibtion, Irfan Hošić did a text for the exhibtion which is, as he says also” thinking about Bihać as a limbo-space caused by territorial restrictions. Methapor-like construction could be extracted as well. From the one side there is hell from where the migrants and refugees are fleeing; on the other side there is also their desired geographic objective (EU); in-between is Bihać. The city became a symbol of enslaved human freedom. It is a social biotope that creates an environment conductive to development of categories of victims and illegality — all under the cloak of NGO humanitarianism.

A text by Irfan Hošić

Introduction

The Didactic Wall by the artist Mladen Miljanović is a subversive educational installation that focuses on the issue of migrants, refugees, displaced persons and apatrids, and the difficulties they face when moving towards their desired geographic objective. This is an engaged set of illustrations that address directly those who, in an “illegal” way, are trying to cross national borders to get to their “land of dreams”. The Didactic Wall is a kind of an instruction on how to overcome natural and artificial barriers an “illegal” person on the move may possibly come across.

The trigger for conception of this work is a massive halt of the migrants and refugees in Bihać as a result of literal closing of the green border by the border service of the neighbouring Croatia to serve as a defensive wall for the Western Europe.[1] The North-Western part of Bosnia is the most protruding and the closest to EU when travelling from the Western Balkans on the way to Slovenia, and as such, it is a logical point for migrants’ settling, gathering, regrouping and rethinking the rest of the travel through the well protected borders of European Union. For the migrants and refugees, Bihać has become a place “on the edge” in the literal meaning of the expression. The place of imprisonment between two realities – one that they are headlessly running away from, and the other – they are madly running to. Essentially, Bihać has turned into a dangerous place that reflects a difficult and unpleasant position of the “people on the move”. Paradoxically, it has become a symbol of enslaved human freedom, although it is a transit location, where migrants don’t want to stay for a long time. A limbo caused by territorial restrictions, all under the cloak of NGO humanitarianism, has created an environment conductive to development of categories of victims and illegality. The triangle between the government institutions, citizens and migrants, in a country like Bosnia and Herzegovina, is determined by establishing repressive control measures, which in turn lead to establishment of inequality in the process of depolitization.

Situation that has evolved over the past few months by activation of the so-called migrant route through Bosnia and Herzegovina is complex, and involves a number of different dimensions – the interest of the EU countries who want to prevent new inflow of “stowaways” at any cost; the interest of Bosnia and Herzegovina, who has no capacities to cope with this challenge; the interests of the migrants and refugees who do not want to stay long term in Bosnia and Herzegovina or Croatia, but hope for a passage to Italy, Germany or other European countries. What adds to particularity of the case in Bosnia and Herzegovina – not only due to the economic circumstances and lack of material capacities in the country to rise up to this challenge – is a very specific and almost complicated internal organization as defined in the Dayton Peace Accords.[2] The new situation with migrants and refugees in Bosnia and Herzegovina has once again confirmed the country’s inability to cope with this and numerous other challenges of a similar kind, what in turn suggests the inexistence of rule of law and security apparatus that would ensure political and social stability of its citizens.

Because of everything stated above, the Miljanović’s Didactical Wall exposes at least three key positions as a kind of three-dimensional interpretative framework. Those are: (a) the artist’s engaged approach that sensitizes our society to the issue of migration, and views the “people on the move” in the spirit of the Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees as a vulnerable social group;[3] (b) the artist’s subversive approach that very deliberately undermines security standards of the government apparatuses; (c) the artist’s (visual art) approach that points at the optics and perspectives that nevertheless may serve as a basis for some form of visual analysis.

When attempting to understand the Didactic Wall, it is impossible to avoid ideological and economic perspectives that imply that the causes of massive movement of people from countries such as Pakistan, Nepal, India, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Libya and others are directly linked to imperialistic and neo-colonial strivings of the developed West. Numerous wars since 11 September 2001, unjustified military interventions, as well as global fiscal malfeasance have caused permanent instabilities in the developing countries. Poverty of African, Asian and Latin American regions is a cause of the global emigration wave that has led to a discrepancy between material hunger at the global North and physiological hunger at the global South. In this context, the Miljanović’s work takes a clear stand that migrants and refugees, as collateral victims of disastrous policies, have absolute right to be accepted, socialized and integrated in the mainstreams of the developed West.

Subversivness of the artistic concept of Mladen Miljanović is seen in the fact of his undermining the idea of borders as a symbol of state-building power that is so easily linked to modern ideas of national and territorial sovereignty. Re-establishment of borders between EU countries has generated a new wave of collective re-identification leading to affirmation of nationalism and right-wing ideas. Abundance of violence by border services (Croatia, Slovenia, Hungary) is a sort of response to fictional undermining the idea of border by “illegal” attempts to cross it. Numerous are the cases of abuse and torture used as a method of systemic intimidation and deterrence from trying to cross the green border again. The practice of organized pushback is in most cases accompanied by hitting and other violent strategies used by Croatian Border Police, and what is of a particular concern is the fact that these are not isolate cases.[4] This habit of the Croatian police – some thirty years after the war – acquires the bitter taste of the conflicts from 1990s – where the ideas of borders responded to ethnic, religious and linguistic divisions in the disintegrating country. Encouraged by Trump’s win in the USA and the Brexit in the United Kingdom, preconditions were put in place in some European Union countries for “emerging social and economic apartheid”[5]

Border as a social narrative

Artistic opus by Mladen Miljanović shows his obvious interest to repeatedly and almost obsessively contemplate the issue of borders. Whether those were geographic borders, as in the case of the Didactic Wall, or social or mental borders that exist in the society where he lives, Miljanović takes the issue of barriers/limits/borders as a kind of backbone to his artwork. Conception of such practice may be linked to his earliest works, like Dobrodišli (Welcome) from 2005, and Služim Umjetnosti (I Serve the Art) from 2006/07. The first one is an explicit reference to the territorial shape of Bosnia and Herzegovina drawn by a hanging rope (possible punishment or suicide), while the latter work is a marathon project that lasted 274 days, where the artist’s body had been pushed to the limits of endurance in a voluntary isolation in the former military barracks Vrbas in Banjaluka.[6] Miljanović continued the practice of testing individual and collective abilities in the performance Na ivici (On the Edge) given at numerous locations since 2011 to date, where he literally hangs at the edge of a fence, while opening of his exhibition is in progress inside the building. His many performances and actions are coded with elements that examine personal or social restrictions, such as Pritisak želja (Pressure of Desires) that was performed on the eve of opening of the Bosnia and Herzegovina’s pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2013, when the artist was holding a heavy marble slate for about an hour and a half, with short messages responding to question “Dear friend, what would you like to see in the pavilion of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Venice?” In his most recent video, Zvuci rodnog kraja (Sounds of the Homeland) he gathers veterans from three warring armies and asks them about the purpose of their engagement in the war during the 1990s, questions the conflicting borders, and relativizes their significance to the level of banality. The common theme of all these works is ironization of the imposed barriers between individuals and groups, and an almost subversive attitude towards social norms and customs that foster and maintain such borders.

The borders as a theme of art is, of course, present in BiH art of other artists too.[7] This reflects the social reality where divisions and restrictions make an integral part of daily life, and in Bosnia and Herzegovina this daily life is marked by series of border systems, such as the two entities, one separate district, and ten administratively separate cantons. This phenomenon has been the object of interest of Maja Bajević, Šejla Kamerić, Veso Sovilj, Gordana Anđelić Galić, Andrej Đerković, Borjana Mrđa, Lana Čmajčanin and others – all of them driven mad by media-enforced theme of divisions in BiH society. From this point of view, the theme of borders suggests that there is a broadly set and rather dominant “real social substance”, because the “borders have become a sign of imprisonment, isolation, division, vulnerability, insecurity, problems and conflicts”.[8]

It is this artistic context where the Didactic Wall has its place, and Miljanović confirms his own rule that art can, but also should be, a criticism of disastrous policies, unethical rules and immoral values. The Didactic Wall is an engaged action that clearly and vocally takes position of sensitive and vulnerable population that has, by chance, been stuck not only in Bihać and Bosnia and Herzegovina, but also in numerous other places on this planet.

Constitution of Didactic Image

The visual language Mladen Miljanović uses originates from military literature of the former Yugoslav People Army. The artist places the educational materials used in the military schools in a completely different socio-political context. His intention is determined by the motive to create a functional and effective instruction for overcoming natural and artificial barriers, such as water bodies, injuries suffered in the wild, fences, infra-red rays, radars, etc. This is a utilitarian pictorial mission with an engaged prefix that is carried out in the medium of didactic illustration.

Such illustrations show a very clear constellation between the subject and object, and the point of view or observation of the presented situation is in most cases identified with the position of the subject. The angle of the projected view “from this side” is significant and suggests the artist’s identification with the subject. Namely, the illustrations show positions “on this” and “on the other” side using the same model that it is undoubtedly clear in military doctrine.

Miljanović’s establishment and determination of constellation between the subject and object does not allow for an avoidance of the issue of medialization of migrants as subjects. The mainstream media contribute to construction of media image of refugees, and often they do so in a wrong way, because they manage to depersonalize and dehumanize them. Therefore, the question of Miljanović’s determination and perspective in understanding of the Didactic Wall is of a central importance for ideological positioning of his own views. If by any chance the point of view had been placed “on the other side”, i. e. that the subject has been placed opposite to the viewer, it would create a visual antagonization. Although they are cold in their expression – as much as the illustrations of this type can be – they are not without emotion, and they are far from depicting migrants as the “others” and the “different ones” and therefore a potential threat, as it has been done in the mass media today.[9]

One relevant question regarding the subject is, of course, “what does he see”, i. e. “what the subject is looking at?”.[10] Miljanović’s Didactic Wall does not concern itself with this direct view, i. e. does not present it, but keeps it in mind nonetheless. In order to emphasize the didactic mission of his task, the artist very deliberately avoids the constitution of an image as seen by first person singular. So he chooses the second person singular and tells the story about the subject from a “didactic distance”, which in turn harmoniously defines the relationship between the object, the subject and the context. This makes the gaze by the migrant coded into the Miljanović’s illustration and the constituent part of the concept on which it relies, without showing it explicitly.

In visual sense, the Miljanović’s illustrations are emotionless. Since this is an educational material, the range of visual expressiveness and expression has been narrowed down to the most basic information. Character of the drawings is determined by tactical norms from military manuals and for soldiers in rear detachment.[11] The mentioned reading material from which the artist “borrowed” the templates has often been labelled by publishers as a “military secret”, suggesting the incriminating potential of the whole artistic project, mostly because the artist translates the military doctrine into civilian purposes. An additional complication is summarized in the fact that those are not “ordinary” civilians, but “stowaways” and “illegal migrants”.

Miljanović choses stone as material that has traditionally implied monumentality. By carving his drawings into such material, he wants to underline the social importance of the message he carves into it and its present significance. The attempt of artistic matching of an idea with selected materials points at the necessity of permanence in preserving its content, and the artist’s desire to avoid the trap of simply documenting a specific problem. He uses his full capacity to advocate for creating an effective instruction and set of methods for overcoming the “migrant crisis”. When doing so, the solidity of stone offers also a sacral dimension, as it inevitably reminds of the Moses’ Commandments that are believed to have been carved in stone as well. In addition, the relationship between the name of the work and the use of the word “wall” is more than obvious. Therefore, the Didactic Wall is an indestructible building and permanent monument to empathy and social responsibility that strives to achieve better society, affirmation of democratic values and human rights.

Conclusion

Earlier, Miljanović has already reflected on the process of transforming elements of military into art in his work Služim umjetnosti (I Serve the Art). His desire from a young age to build a military carrier has been weakened by processes of demilitarization of army structures of Bosnia and Herzegovina immediately after the war. As a young cadet of the military academy in the barracks Vrbas in Banjaluka, he saw the acceptance of the new profession of an artist as the only scenario after the military barracks were transformed into an Academy of Arts. This has turned Miljanić into an alchemist who transforms the elements of military into elements of a social sphere. Therefore, the Didactic Wall is a very valuable contribution to the society – a pacifist and human oriented tool that has emerged from destructive and militant didactics of sophisticated wars of today.

[1] Any reminiscence of the wording by Pope Leo of the 16th century about Croatia as the bulwark of Christianity (Antemurale Christianitatis) standing against invasion of the Ottoman forces is purely coincidental.

[2] Main characteristic of the unique organisation of Bosnia and Herzegovina is its ethnic regionalization stemming from experiences of genocide committed during the war in 1990-ties, odd parliamentary setup with three presidents, etc.

[3] “Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees” in: UNHCR, 1951. Document available at: https://www.unhcr.org/3b66c2aa10 (last accessed on 8 March 2019).

[4] “Croatia: Migrants Pushed Back to Bosnia and Herzegovina” u: Human Rights Watch, 2018. See: https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/12/11/croatia-migrants-pushed-back-bosnia-and-herzegovina (last accessed on 9 March 2019).

[5] T. J. Demos, The Migrant Image. Duke University Press, Durham and London 2013. P. 246.

[6] Služim umjetnosti (I Serve the Art) by. Mladen Miljanović, Boško Bošković (ed.). Besjeda, Banjaluka 2010.

[7] Irfan Hošić, “Granica kao metafora. Šta je to ‘bosanskohercegovačka savremena umjetnost’ (2)” in: Iz/van konteksta. Connectum, Sarajevo 2013. Pp. 132-140.

[8] Irfan Hošić, “Bosnian and Herzegovinian contemporary art and a resurgent question of context” in: Duplex 100m2 (Pierre Courtin, ed.). Sarajevo, 2019. Pp. 36-39.

[9] Sara Kekuš, Davor Konjikušić and Petra Šarin, “Uloga vizualnih narativa u konstruiranju slike migranata – poziv na solidarnost ili depolitiziranje masa?”, in: Kamen na cesti: granice, opresija i imperativ solidarnosti. Centar za ženske studije, Zagreb 2017. Pp. 114-123.

[10] Irfan Hošić, “Pikselizirana trauma između fikcije i realnosti”, u: Oslobođenje, 10.8.2018. Sarajevo 2018. https://www.oslobodjenje.ba/o2/kultura/pikselizirana-trauma-izmedu-fikcije-i-realnosti-384495 (last accessed on 22 May 2019).

[11] Taktika, Savezni sekreterijat za narodnu odbranu, Beograd 1983.; Priručnik za komandira odeljenja, Savezni sekreterijat za narodnu odbranu, Beograd 1988.; Priručnik za vojnike pozadinskih službi JNA, Savezni sekreterijat za narodnu odbranu, Beograd 1990.

July 18th

Artwork: Worth of gold when a home is made, 2007

Artist: Saša Tatić

The artist’s description of the artwork:

Old bricks, that were previously used as a material for construction of a house, still hold the potential for its recreation, a habitual place commonly accepted as home. As the identical content of two photographs, with a small intervention that created ‘before and after’ relation, they ask for recognition of fundamental values which under the flux of life often stay hidden and forgotten.

My free reflection on the work:

This artwork of Saša Tatić carries a concept of potential in a possible construction, but visually, the bricks in her artwork remind me as much of construction elements as they remind me of ruins or something related to deconstruction and rebuilding. This is probably why the Tower of Babel came to my mind, not religiously, but rather as a model for thinking about language, which can lead to a mutual understanding as well as misunderstanding.

According to the legend, the story about the Tower of Babel goes back to the time when all people spoke the same language and humanity was united to initiate a common building project explained as such in the book of Genesis, Chapter 11 :“Come, let’s make bricks and bake them thoroughly.” They used brick instead of stone and tar for mortar. Then they said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city, with a tower that reaches to the heavens, so that we may make a name for ourselves; otherwise we will be scattered over the face of the whole earth.”

The Tower of Babel remained an unrealized idea, as God chose to punish humanity for its hubris by splitting the language common to all people into many different languages. The penalty came with this explanation: “Behold, they are one people, and they have all one language, and this is only the beginning of what they will do. And nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them. Come, let us go down and confuse their language so they will not understand each other.”

After the split, the people could no longer understand each other, and thus the Tower of Babel was never built. The linguistic division today is not only traceable in terms of language differences in the world. This unfinished action has also left us with ruins that have implanted some sort of nostalgic loss into our view of history.

The ruins are important images for the understanding of the world today, and there are two distinct views of ruins. One of them is rooted in a transcendental worldview vertically pointing towards God or another greater power, while the other can be called horizontal because its worldview is placed on the immanent level. The greatest difference between the allegorists and the symbolists is based on their different concepts of history.

A beautiful image of the allegorists’ melancholy associated with the history, can be found in Swiss painter Paul Klee’s angel, who Benjamin in 1940 called the Angel of History and described in the following way: “There is a picture of Klee called Angelus Novus. It depicts an angel who looks as though it was getting away from something it is staring at. Its eyes are obscured, its mouth is open, and its wings are wide. This is how the angel of history must look. It turns its face toward the past. Where, for our eyes, there is a chain of events that sees the one catastrophe that incessantly piles up ruin on ruins and throws them at the angel’s feet. It wanted to stay, wake up the dead and add it back together. But from Paradise, a storm that has its wings blowing and is so fierce that the angel can no longer fold them. This storm drives it relentlessly into the future as it turns its back, while the ruins in front of it grow into the sky. What we call progress is this storm.”

Contrary to the allegorists, the symbolists mostly interpret ruins as remnants of a whole that have occurred once in the past, and therefore (at least potentially) as remnants that may well be recreated. We could, therefore, say that the symbolists are spokesmen for a transcendental worldview and that the languages for them always have a clear reference to the “common human language” – also called “Adamic language” because it (according to Chistianity) is the language Adam spoke in Paradise to communicate with God and name the animals. This kind of language is based on pure and immediate communication – language without grammar or accents, based solely on the use of language (parola) and not the language structure (lingua).

Since Adam was expelled from paradise, the language has degenerated so that today we only experience incoherent fragments of it. The symbolists’ mission is to return to the true expression of the original language by mapping the many world languages in a hierarchical system according to their respective degrees of authenticity (or how close to the language they come). – The search for the original Adamic language takes place through empirical analysis and techniques where one attempts to map the history of language by looking at changes in, for example, bending forms and sound shifts. This science and research is driven by the idea of a common human past where there was a perfect language in which the sign and signification were assembled in an almost magical and divine primordial archetype image possessing an archaic character and expressing something beyond itself.

Returning to the image of the Tower of Babel, one could say that the symbolists’ mission is to rebuild the Tower of Babel by bringing fragments from the ruins together in a solid, upwards-striving tower with a harmonious and perfect expression depicting the transcendental idea.

The picture of the tower I would like to refer to is not the image of a solid tower, but a picture of the broken tower.

In the ruins of the tower, as you can see from the picture, there are a lot of remains in the form of bricks and parts of the wall that randomly lie in a pile. Maybe the only right way to navigate the world is to move between this rubble. Instead of re-connecting the remains, one could “draw” a connecting line between the fragments.

In the ruins of the tower, as you can see from the picture, there are a lot of remains in the form of bricks and parts of the wall that randomly lie in a pile. Maybe the only right way to navigate the world is to move between this rubble. Instead of re-connecting the remains, one could “draw” a connecting line between the fragments.

This would not be a connection that closes itself in one whole, but an open construction under constant change. The many sub-elements in the tower that symbolically each represent a language in the world may be related to each other again – not in the form of a vertical structure like a tower that strives for the sky, but as a network moving in the margins of tower- ruin.

Maybe in these lines we can sense a common human understanding that is not an “original language”, but another type of community based on linguistic inconsistencies and misunderstandings. And thus, it would be one that consists of a common alienation to each other’s respective languages. The untranslatable and the invisible elements of language could maybe serve us in imagining unity in the linguistic differences and cultural diversity.

July 17th

Artwork:

Artist: Amel Ibrahimović

The artist’s description of the artwork:

The artist’s description of the artwork:

The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction by Walter Benjamin(1935): »Buildings have been man’s companions since primeval times. Many art forms have developed and perished. Tragedy begins with the Greeks, is extinguished with them, and after centuries its ‘rules’ only are revived. The epic poem, which had its origin in the youth of nations, expires in Europe at the end of the Renaissance. Panel painting is a creation of the Middle Ages, and nothing guarantees its uninterrupted existence. But the human need for the shelter is lasting. Architecture has never been idle. Its history is more ancient than that of any other art, and its claim to being a living force has significance in every attempt to comprehend the relationship of the masses to art. Buildings are appropriated in a twofold manner: by use and by perception – or rather, by touch and sight. Such appropriation cannot be understood in terms of the attentive concentration of a tourist before a famous building. On the tactile side there is no counterpart to contemplation on the optical side. Tactile appropriation is accomplished not so much by attention as by habit.«

Bosnian House Konak (2012 revised 2017) is Model House design in collaboration with Maria Engholm 2012 Iben Bach 2017

Photo credit: Torben Eskerod 2017 Marcel Stammen 2012 revised 2017 Anja Franke 2012

The project is supported by the Danish Art Workshops

My free reflection on the work:

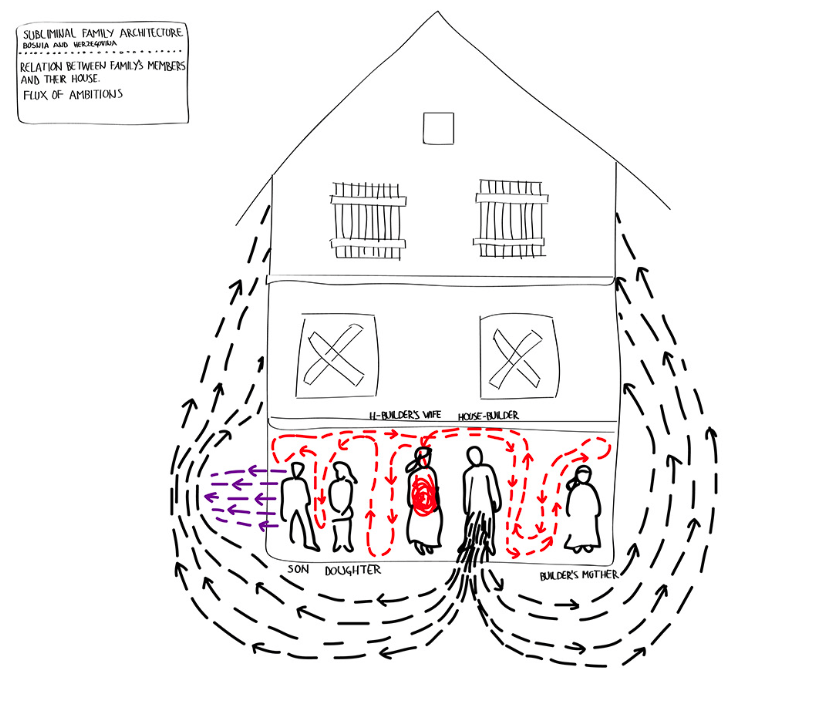

Konak is a word that refers to a guesthouse. And when we say “na konak”, it means to sleep at someone’s place. Konak is about hospitality offered by the host to the guest – the generous welcoming gesture in the form of a place to stay. It’s the idea of an ultimate Bosnian house; Konak is thus also the idea of Bosnian hospitality, a quality one could question, especially in today’s context where border towns like Bihac are facing waves of refugees from the Middle East without always receiving them with hospitality.

The artist inherits the concept, and probably also the symbolism, of the house from his father. He transforms the drawings made by his father into a three-dimensional model. The drawing lines made by the artist’s father in Bosnia, before the war, are many years later translated into construction elements developed by the artist in Denmark, where he escaped to as a refugee. In this process, the idea becomes more concrete. Nevertheless, the model is still only a sketch; it is not a real house. Maybe this ideal house should never become a real house. Maybe it should remain as a model of potentiality maintaining the aspect of not yet realised possibilities.

We could describe Potentiality in following way (inspired by wikipedia descriptions of Physics (Aristotle)

Potentiality and potency are translations of the Ancient Greek word “dunamis”, as it is used by Aristotle as a concept contrasting with actuality. Dunamis is an ordinary Greek word for possibility or capability.

In his philosophy, Aristotle distinguished two meanings of the word dunamis. According to his understanding of nature, there was both a weak sense of potential, meaning simply that something “might chance to happen or not to happen”, and a stronger sense, to indicate how something could be done well.

Throughout his works, Aristotle clearly distinguishes things that are stable or persistent with their own strong natural tendencies towards a specific type of change, from things that appear to occur by chance.

He treats these as having a different and more real existences. “Natures which persist” are said by him to be one of the causes of all things, while natures that do not persist “might often be slandered as not being at all by one who fixes his thinking sternly upon it as upon a criminal”. The potencies that persist in a particular material are one way of describing “the nature itself”. According to Aristotle, when we refer to the nature of a thing, we are referring to the form, shape, or look of a thing, which was already present as a potential with an innate tendency to change in that material before it achieved that form, but things show what they are more fully, as a real thing, when they are “fully at work”.

July 16th

Artwork: House Museum, 2007

Artist: Katarina Šević